Technological innovation is as old as humanity. Technology can be a physical creation or a process, anything that increases the scope of possibility or improves efficiency.

First and foremost, I am unabashedly pro-technology, and despite the side this paper takes, I wish for its progress to continue or accelerate. I will explain why the extreme anti-technology side is mistaken with a hypothetical victim, Dan. Suppose Dan manufactures nails professionally. Someone else creates a technology that allows them to manufacture nails twice as efficiently as Dan does. That person can undercut Dan with a reduced price. Dan himself may want to adopt the technology, but we can assume that is impossible because of patents or other reasons. Dan’s living is being stripped away – at least that is what we would assume. Except that, assuming technological progress is widespread rather than localized, every other product in the economy is also being sold at reduced price. By whatever amount Dan’s revenue is being reduced, everything he buys is having its price cut by the same proportion. This is of course an oversimplification, but it shows that whatever is the value of a nail, Dan may always be compensated that amount. Technology may or may not help Dan specifically, but in aggregate, all those like him across the economy are not hurt by technology. They are only having their methods rendered so antiquated that they would be better off spending their time on something other than creating nails. But technology brings a unique set of challenges

Technologies make human labor easier or replace it altogether. When technology replaces labor, it is called automation. When an entire industry is automated, the result is called structural unemployment. This hurts many in the short term, but economists generally accept that technological change helps the majority in the long term. Throughout history, as old jobs were destroyed, new jobs manifested themselves over time in similar proportion. But some argue that in the future jobs will be destroyed faster than they are replaced. They claim that unemployment resulting from technological change, “technological unemployment”, will shape the economy in the years ahead.

A post-scarcity world is a world where no one wants for anything, because the economy is at infinite capacity, and everything is free. It is easy for science fiction to imagine this is what automation will bring. But post-scarcity is only a thought experiment, possibly not achievable even in theory. Technological improvement will not make things free, only cheaper. But what good are cheap prices if automation leaves many people unemployed and therefore without money, or otherwise not able to share in the existing prosperity?

You may be aware of the argument popularized by CGP Grey, mocked by the name “humans are horses argument”. I have come to agree with CGP Grey, and in the interest of representing the argument fairly, I have read a more academic version of it.

In his paper, BIG and Technological Unemployment: Chicken Little and the Economists, Walker argues that technological unemployment will be a large problem soon. He is aware of the objection that such a claim has been previously mistaken. He calls this Economist’s objection. He calls his own case, that this time will be different, Chicken Little’s case. Walker uses the analogy of horses. Horses once held jobs mostly related to physical labor. Now they only hold a small amount of jobs mostly related to nostalgia. Horses offer two main things: physical labor and nostalgia.

One can make a parallel to humans, but humans are different. As well as physical labor, humans can partake in mental labor. For the last century, physical labor jobs have been disappearing. And in that time, people have been too soon to claim this will create technological unemployment. That does not come to pass because workers move from physical jobs to mental jobs. Factory work is replaced with the service industry. Even driving, for instance, requires a mental decision-making process.

But now, computers pose a paradigm shift; because of computers, even mental jobs risk being automated. Robots that replace physical tasks must be complemented by human watchfulness, but the same is not the case with respect to mental tasks. Due to the introduction of computers, the sky really is falling.

Autor explains “Moore’s Law”, the principle that computing power doubles roughly every year. Whatever problems machine learning has now, it may not experience in the future. It is worth noting, however, that even if Moore’s law is not true, technological unemployment may still be something to fear. All that is required is (A) machine learning and/or computing technology more generally will continue to improve, and (B) there is no job that a computer cannot in theory do. As long as both A and B are true, there will come a point when any job that humans could possibly do will be automated. I see no reason to doubt either assertion.

Many high-flung academics who argue that the destruction of some jobs will just lead to the creation of better ones. I have noticed, among these academics, a certain scorn for what they describe as “physically demanding, repetitive, dangerous, cognitively monotonous work”. They do not think the replacement of this work with robots to be a great loss. But this neglects to imagine that for some people, that is the only work they are capable of doing. They would value, for instance, the job of scientist over that of assembly line worker, but that is their bias as intelligent academics: the preference for the more cognitively demanding job. Some people may not be cut out to be scientists. For such people, the job replacement phenomenon is not a blessing but a curse. There are great jobs available, just not for them.

The effects on inequality can be seen. There was a time when more intelligent and less intelligent people worked about the same jobs. Even geniuses were usually destined to plow a field alongside their neighbors. Today, by contrast, the more gifted can make a lot of money as physicists and programmers, while jobs like farmer (which once could support a family) is no longer as available as it was, to the detriment of the non-gifted. I propose that this is a problem because an enormous amount of prosperity is being created, but it is only available to the select few, those who go to the best colleges and are compensated in a manner befitting of the economy. Perhaps the only “work left to be done” can only be done by a small number of very cognitively skilled people, and we are blind to this fact because everyone else is given grunt work, keeping up the appearance of employment. This is called the cognitive stratification of society.

I agree with the problem that Autor predicts, but not his solution. Autor proposes Universal Basic Income, which he calls a Basic Income Guarantee, whereby everyone receives money from the government unconditionally. He explains that it will be affordable with a value-added tax. I call it Universal Basic Income (UBI) like a regular person. I have two principal objections to his proposal.

First, I admit that UBI, if implemented correctly, is superior to our current welfare system.

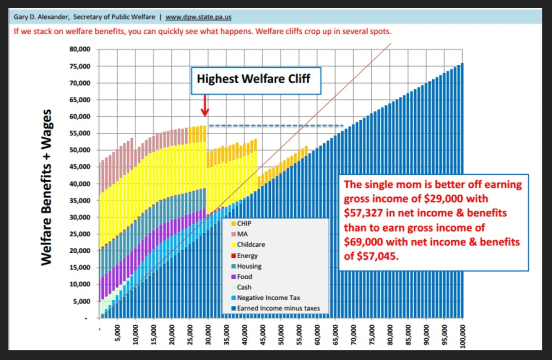

The current welfare system:

Sorry for the poor quality of this image. Since I found it online, I cannot attest to the exact accuracy of the graph, but it illustrates a general principal: the poor mathematics of the system. It might seem confusing; the x-axis represents income, and the y-axis represents spending money + benefits. There are “welfare cliffs”, where getting a higher income can actually reduce your quality of life.

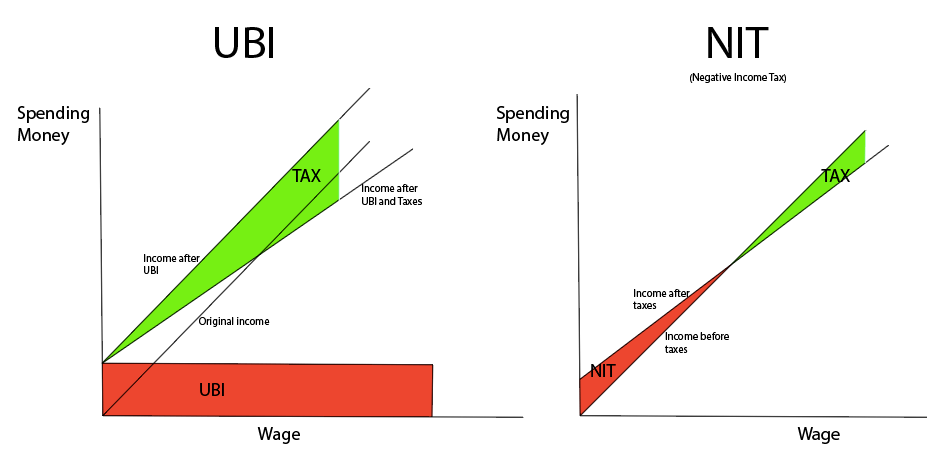

UBI corrects this:

As you can see, there are no “welfare cliffs”.

But there are two problems. Firstly, UBI is easy to implement incorrectly, and it must be implemented perfectly to work well. I have no confidence in the ability of politicians to impalement it well (much less perfectly).

For example, UBI only works if it replaces the old welfare system. If it is simply layered on top of the current welfare apparatus, it will simply compound the existing problems rather than correct them. As another example, UBI must be paid for by a flat tax or equivalent, like a VAT, whereby every dollar made by anyone is taxed at the same rate. If that is not the case, it is not really Universal Basic Income as it is typically sold.

These are common points of confusion, which is why I think we should implement the proposed program as a negative income tax rather than UBI or any other variant. A negative income tax is effectively the same policy as UBI, but it is implemented differently. Whereas UBI taxes money away and then “gives it back”, a negative income tax calculates the net effect that UBI would have and puts that directly into effect. This makes it less prone to implementation problems.

In fact, the graph I originally showed you was not actually a graph of UBI. It was a graph of NIT. I think this is an important point, so I’ve created this comparison:

My second criticism of UBI is that, although a more cynical view would state otherwise, work is more than just a transaction of goods and services for money. Payment is not the only benefit derived from labor. Work gives us the fulfillment of knowing that we are spending our time on a constructive pursuit. We see what happens when people do not spend their time on constructive pursuits: they become isolated, depressed, and in extreme cases join gangs.

With this in mind, some have propose as a welfare program a federal jobs guarantee: anyone who wants a job can apply and will be given a fixed-wage job by the government, regardless of skill.

A federal jobs guarantee completely avoids welfare’s incentive problem. Even with UBI, the jump from living off welfare to working is such a change of time commitment that many may not think it to be worth it. A federal jobs guarantee, by contrast, could never dis-incentive working, because to receive anything, you have to work. Of course, we would have to iron out exceptions for people unable to work due to disability or old age; perhaps we could allow UBI only for such individuals.

But what of a world where robots can do virtually all jobs, what tasks should the job consist of? The government can make up useless tasks, but an objection is that this is degrading and will actually contribute to meaninglessness.

The ideal welfare and unemployment remediation system would pay people for carrying out a task that (A) anyone can do (B) has undeniable value, and (C) cannot be automated. There is only one thing that fits all three of those roles: Exercise. Virtually anyone can exercise his or her body in some capacity (we can make exceptions for those who cannot). Exercise has undeniable health value, and could curb the obesity epidemic. Finally, exercise cannot be automated, because it is by definition something that occurs with the human body.

Exercise is just the right substitute for work because it is time consuming, fulfilling, and positive-sum. Therefore, I propose a welfare system whereby people are paid for meeting a seasonal athletic requirement in their chosen sport. For example, running a mile in under a specified time.The requirements should be written such that anyone able-bodied can achieve them with 30 hours a week of athletic training. I am aware that some people will start out less physically fit than others. We can take this into account by giving a passing score to anyone who improves by objective measures from the previous season. Currently, only a small number of athletes can make a living form performing, but with government stipend, I want to expand that to anyone.

The improvement of technology is good and part of being human. But we should not anticipate a post-scarcity world. Instead, consumer products will still have a cost, and only a few people will be employed with good jobs. Technological unemployment will shape the world ahead. Walker explains how automation is different now than it was before. I suggest that Walker’s solution, UBI, is suboptimal, and propose a policy where people are paid for exercise. My proposal will alleviate many problems of technological unemployment, and bring people more than just money.

Man a brilliant idea. Though I do think government is unnecessary.

There is also another fulfilling task anyone can do – self improvement. Life is more than work.

No one in developed world is in danger of dying from hunger. Food and shelter is cheap(if you don’t insist on status signaling). Without govt interference it would be even cheaper.

So more automation there is- less time people need to spend working to cover necessities and more time working on yourself.

While living in US I noticed that there are no shortages of opportunity or money for everyone. But people who are “poor” rather whine about the perceived disadvantage as they can’t afford expensive status signaling.

They live in govt appt(very high quality) and buy latest iPhones. Drive expensive cars and use foodstamps. They often lazy and entitled.

LikeLike